Strategies for Beats

It has been quite some time since I wrote about Spotify and Beats, so let’s briefly step aside from the automotive and tech posts and into music. Some fairly important news got lost in the Apple Watch shuffle last week — music labels aren’t willing to go below $9.99 per month for music streaming. The most interesting information is tucked away in the last paragraph of the Billboard article (emphasis mine):

There’s also an element of geopolitics at play. A weakened Spotify could help create a more powerful Apple subscription service. That would remove the comfortable, valuable counterweight to Apple that labels don’t have in the digital download space. There’s even some doubt that Apple is out to beat Spotify rather than grow the music subscription marketplace. “If they’re out to kill Spotify, it’s news to us,” says an industry source. "And it’s the last thing we want. We want Spotify to be a strong competitor.

Spotify is king when it comes to music streaming — it has around 15M paying subscribers, and 60M free users. Probably the most important variable to Spotify’s growth is that it allows you to use the desktop apps for free, which is always the preferred option. Spotify is available in most countries and practically on every platform. It was also one of the first entrants in the play-on-demand business (Pandora doesn’t allow for this), which undoubtedly gave it a first-mover advantage in terms of total users.

Unlike what smartphones have become today, music streaming is a luxury that not every person needs. Therefore, the total market size for paid-for music streaming is quite limited. Although Spotify + Rdio + Deezer + Rhapsody have much more room to grow their paying subscribers, that growth is slowing down. The best way for Beats to grow is either to convert existing iTunes users into paying subscribers (a challenge made even harder if that user is already paying for a competing service), or to steal market share away from Spotify/Rdio/Deezer/Rhapsody. The best way to steal market share would be to offer Beats at a lower monthly price ($7.99), which reports suggest Apple has tried to do and failed. The music industry doesn’t want to make the same mistake as it did with iTunes, which allowed Apple to become a monopoly on music sales. The more competition exists, the more bargaining power the music labels have over steaming services. Since it is unlikely Apple will convince the labels to a lower price tier, Apple must find a different way to grow the Beats brand into the next iTunes. Here are some strategies I would advise Apple to partake with Beats (preferably more than one):

#1 Take the hit

Just because the music labels won’t go lower than $9.99 doesn’t mean Apple can’t. There is always the option of taking the difference ($9.99 - $7.99 = $2) as an expense, thereby subsidizing users. It’s doubtful that existing users of Spotify/Rdio/etc will be enticed purely by the features of Beats, which might be less expansive (compared to the competition) when Apple’s redesign of Beats goes live. A user of Spotify myself, I’ve been extremely impressed with the latest updates to their apps (ample gesture support, song lyrics, and the overall design aesthetic), and I can’t imagine the first version of Beats to be as fully fleshed out. Although features themselves won’t entice users to switch to Beats, a slightly lower price of $7.99 surely will. Finally, it’s worth pointing out that most of the existing streaming services offer a 50% student discount, effectively making the monthly price $4.99. I use this discount, and I know many other friends who do the same. Beats doesn’t currently offer any student discount, but they will have to if they want to reach the price-conscious college age audience.

#2 Exclusives

There is a new Kanye West album coming out later this year. What if Beats were able to snag it as an exclusive for the first month, thus having it before all of the other streaming services get it. That would be a very powerful value proposition, and one only Apple can negotiate. Of course Kanye wouldn’t be the only artist Beats would have exclusive rights to — they should negotiate similar exclusivity rights for as many artists as possible. If you knew that your favorite artists new album will only be available on Beats for the first month, you sure as hell would consider switching to Beats. It should be noted that these type of deals are expensive and difficult to negotiate, but Apple has money, and money talks.

#3 Preinstalled with hardware

Apple has complete control over the hardware and software of its products. Just as the the music app is bundled with all devices, so should Beats. The Beats app should come preinstalled on the iPhone, iPad, Mac, and the Apple Watch. This will serve two main purposes. First, it will cement the brand name. Most people aren’t as familiar with Beats music streaming as the Beats headphones, mostly because the service has done very little promoting of itself. Coming preinstalled with Apple hardware would certainly fix that.

Deriving from this first benefit of being preinstalled on hardware is the second benefit — increased usage of Beats. If more people are aware of the Beats music service, it is logical to assume more people will use it. Where these users come from doesn’t matter; it may be those uninitiated to any music streaming service, or those switching from Spotify/Rdio/etc.

#4 First-party advantages

As the software chieftain of its products, Apple can use API’s not available to 3rd party streaming services. You don’t need to search too hard to find miffed developers complaining online about their apps not being able to using the same API’s Apple uses in its apps. These API’s are locked from 3rd parties for safety and privacy reasons, but they allow for many functions regular apps simply cannot do. It’s still not clear how Spotify will work with the Apple Watch, but I imagine the limitations will be plentiful. For one, the Apple Watch comes with 8GB of storage, but only 2GB are available for storing photo’s and music, with the remaining 6GB used to store the OS. Perhaps the Spotify app will be limited to offline storing of only 2GB of music on the Watch. Meanwhile, the Beats app will allow for more, since it will be graced with Apple’s first-party stamp of approval. This is all conjecture, of couse, but you can bet that Apple will use 1st-party API’s to allow for more features that 3rd party apps can only dream of.

Précis

I have many more ideas for what Apple should do with Beats to make it overtake the other streaming services, but we can leave that novella for a later time. The four strategies I have listed above are the most vital to the success of Beats. So vital, in fact, that I don’t think Beats will succeed unless at least two of the four options will be chosen. Realistically, options 3 and 4 will be implemented by Apple, mostly because they come with no additional costs. I do not think, however, they will be enough to convince people to switch to Beats. To steal market share from the other music streaming services, options 1 and/or 2 should be chosen. They will likely cost an additional few hundred million per year, but I think those costs will be indemnified by the goodwill they generate, and the influx of new, paying users.

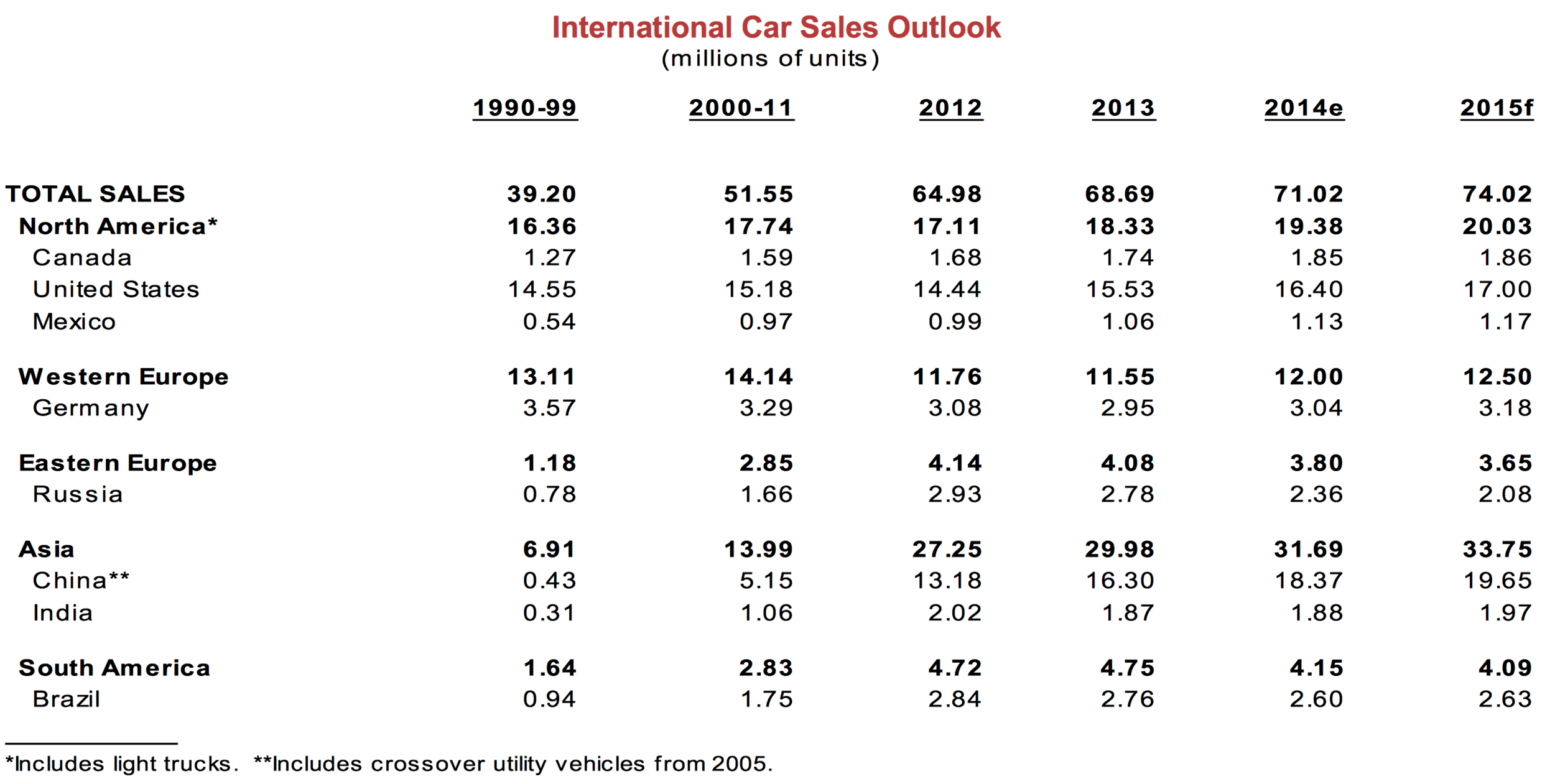

For next week, we will continue our automotive industry discussion by comparing the unit sales of the major automotive manufactures.

If you have anything to add, or just want to share your meandering thoughts about what we covered, please comment below! I’m also very active on Twitter, so don’t hesitate to @lsukernik me!