Automotive Industry Exploration (Part III)

In Parts I and II of our Automotive Industry Exploration, we took a look at the revenues and costs of some of the largest players in the automotive world. We found that industry profits are quite low compared to those Apple is used to, mainly due to the intense costs of manufacturing a vehicle (materials, labor, equipment, etc). We also noted that if Apple were to enter the business of manufacturing cars, they would need to introduce some new technology into the equation. That new technology could come in the form of production efficiencies, new use cases, or something we cannot currently surmise. If not for this missing piece, Apple would be just like every other car manufacturer - high revenues, high costs, and average margins. If that doesn’t sound enticing to you, you might be right. It probably isn’t (for you and Apple).

For Part III of our exploration, we will be delving into the unit sales of the car manufacturers we visited previously. If you are like me, your best educated guess about which car brand is the most popular came from what you saw on the streets of your city, which may not be the most accurate data. After comparing the unit sales of the car manufacturers, we will dive into the unit sales of only one company: BMW. This choice was made for a few academically valid reasons. First, BMW is my favorite car manufacturer. Second, they gave the clearest breakdown of unit sales by car model (1 Series, 2 Series…). Third (and perhaps most arguable), out of all the car companies, BMW is most like Apple. They value design, they make premium products that are still affordable by most of the middle-class, and finally, they sweat the details. Part III will be the final post in this three-part series on the automotive industry as a whole. In future posts, we may explore some car companies independently (Tesla, Daimler, Volkswagen) and in greater detail, as well as keep a tab on what is happening with the Apple Car.

Big Picture: Automotive Industry

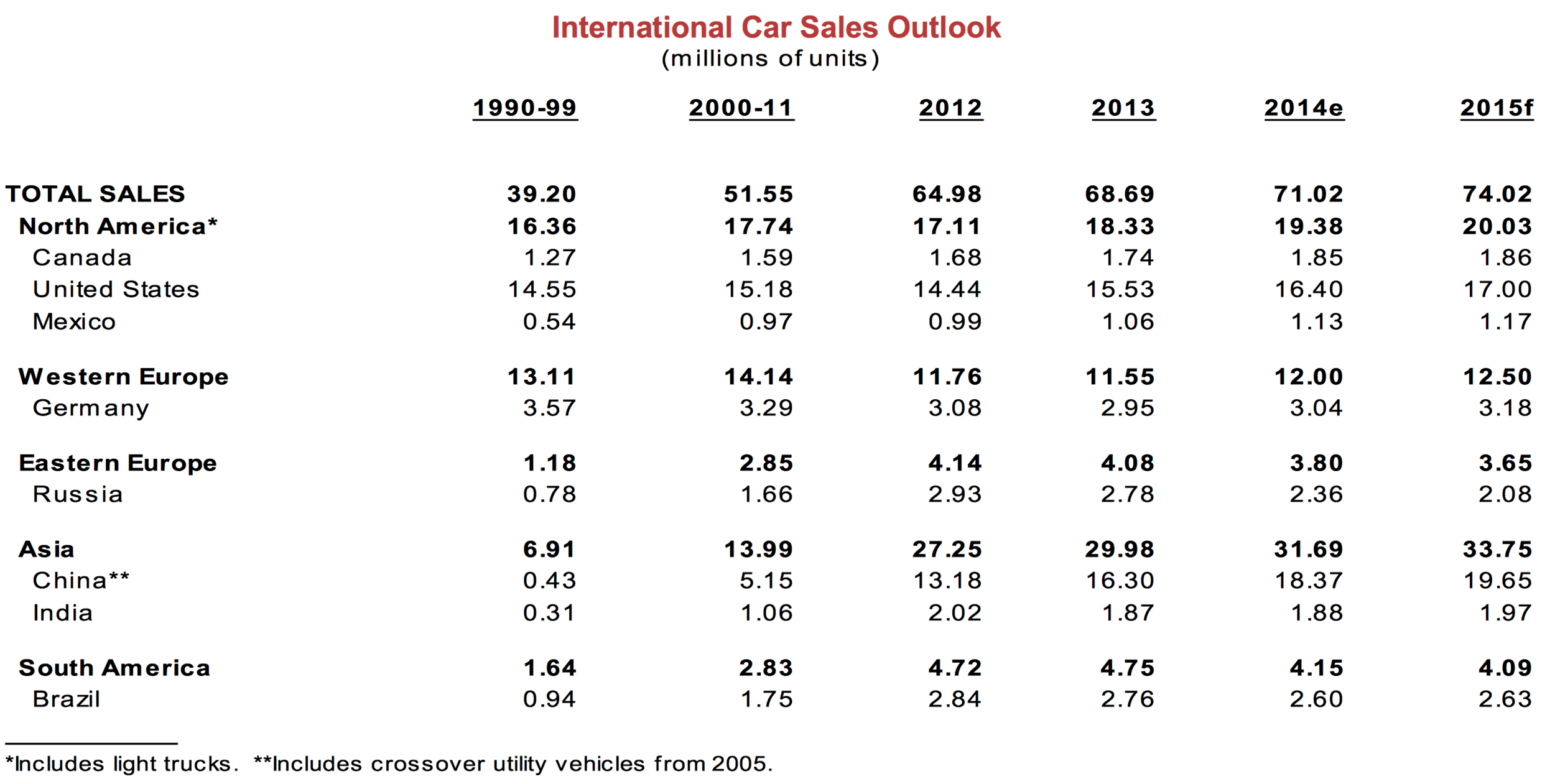

The companies in this chart sell roughly 60% of all the cars sold in the world. Estimates of global car unit sales range from 72M - 84M in 2014, and this chart covers 48M of those sales, hence 60%. If we assume the world population is 7 billion, then we can say that around 1 out of every 100 people buy a new car every year. In reality, that statistic is lower, but the thought is nonetheless intriguing. Some other points:

- Toyota simply dominates the other car manufacturers: it sold 1.2x the cars of Volkswagen, 1.4x Ford, 2.1x Honda, and 4.3x BMW.

- The German luxury brands (BMW & Daimler) together sold 3.7M vehicles in 2014. In terms of unit sales, they are positively paltry compared to the Japanese (Toyota, Honda, Nissan) and American (Ford, GM, Chrysler) titans. If we add Audi unit sales to 3.7M (since Audi is also a German luxury brand part of the Volkswagen Group), that number will equal roughly 5M. German luxury cars thus account for approximately 6% of global car sales.

- For such an old industry, there is surprisingly lots of competition in the manufacture of cars. Although it is true that many car companies have over time consolidated (i.e. GM produces Buick, Cadillac, Chevrolet, and GMC), no one brand controls over 20% of the global market share. For consumers, this is great news. But if you’re thinking of getting into the car business, you better step up your game, because there’s plenty of competition.

Small Picture: BMW

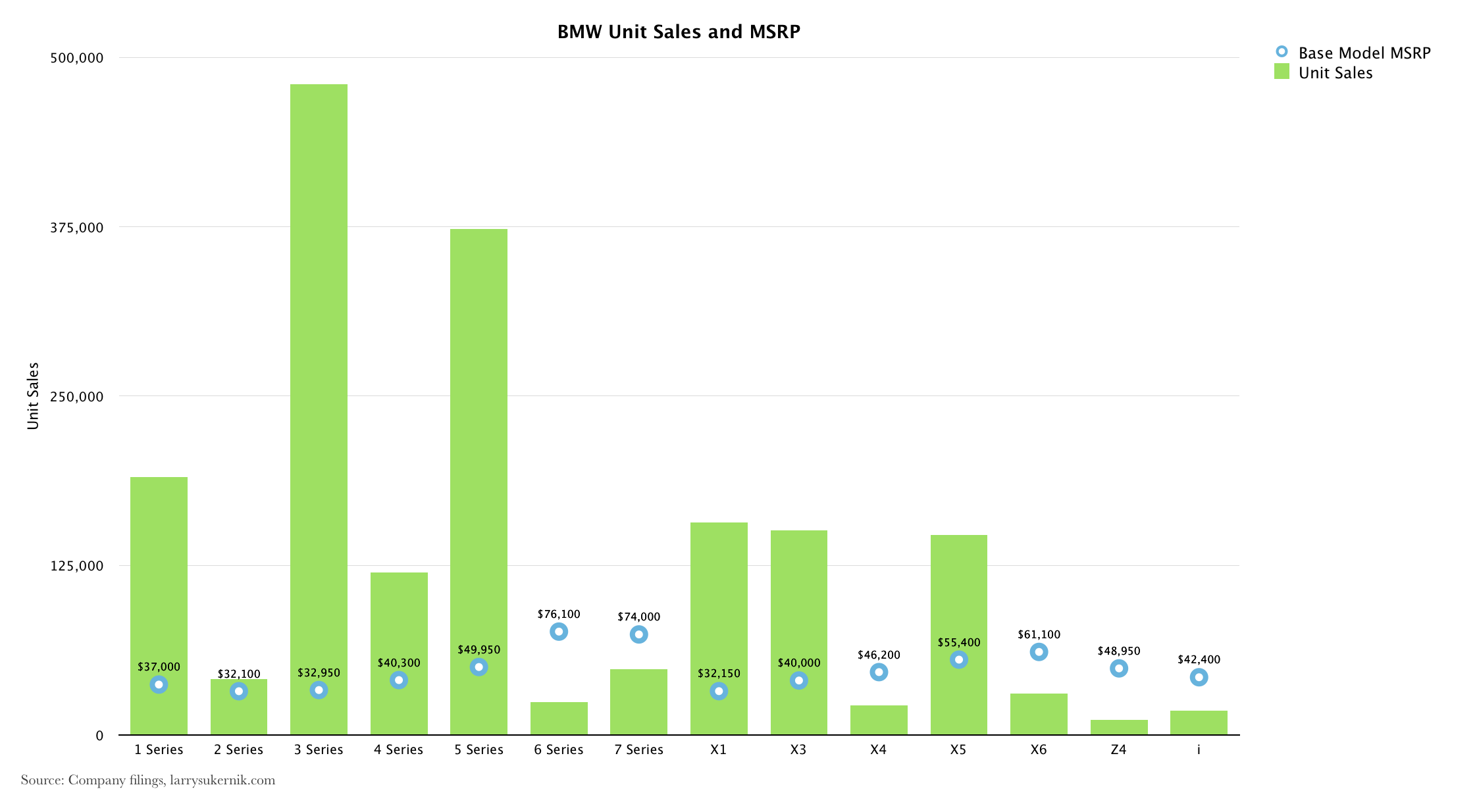

In total, BMW sold 1.8M cars in 2014. The above chart gives us a breakdown of those unit sales, model by model (BMW uses the word “Series” in substitute of model). A few things stand out in particular:

- The 1, 3, and 5 Series alone account for 33% of BMW’s unit sales. They are by far the most popular cars BMW produces.

- 70% of BMW’s unit sales are from compact cars (Series 1 - 7). 29% of the unit sales are from SUV’s (X1 - X6, no X2 exists yet). 1% is from the BMW i, which is their electric model.

- If you wanted to compete with BMW, you could strike from one of three places (or all three, if you’re feeling audacious). You could attempt to steal from their most lucrative business, luxury compact cars, since there’s a huge market for them. Alternatively, you could make luxury SUV’s. Finally, and probably the best choice, you could make electric cars. BMW only sold 18K i cars in 2014. Perhaps there is no demand for them, or, most likely, BMW is underserving the market for electric vehicles. If Apple were to enter the car business, I’d wager they would produce electric vehicles (you will recall I am not a betting man though, so rest assured that your money is safe).

This chart is the same as the last, but it adds one additional detail - the base MSRP of each BMW model.

- With few exceptions, it would be fair to say that the cheapest models sell in the largest quantities. Meanwhile, the most expensive models sell in predictably lower quantities. If you asked me, I would venture to say that the supply for low-end luxury cars matches demand. The supply of high-end luxury cars also seems to match the demand for them.

- BMW covers a wide area of the pricing spectrum: the lowest MSRP is $32,100, while the highest is $76,100 on the opposite side of the spectrum. Of course, these prices are not at all indicative of what you will actually pay for a souped-up BMW - that price will be much higher. Still, I find it interesting how diverse the pricing is for a luxury car. It is much less surprising now to see that Apple Watch pricing is similarly spread out over a large area ($350 - $17,000).

Coda

Overall, the car market is a competitive and somewhat unfriendly place to do business. If you had billions of dollars lying around and were interested in starting a new business, it is doubtful the automotive industry would be it. The profits are decent, but the costs and barriers to entry are huge (but not insurmountable, as Tesla has proven). Moreover, not that many cars actually get sold every year (around 78M). If you want to compete in this business, you’re not going to make much money using economies of scale, since margins aren’t good. The best way to make money in this industry is to be extremely efficient (Toyota, Honda), or to charge premium prices (BMW, Daimler). Even the efficient brands manufacture premium versions of their vehicles: Toyota makes Lexus, and Honda makes Acura. What you don’t want to be is Ford, GM, or Chrysler, which are neither efficient nor have successful premium brands (Lincoln and Cadillac barely qualify as such). As our previous analysis has shown, the American car companies are some of the least profitable car companies around, so replicating them is a fool’s errand. You can, however, make a healthy profit selling premium cars, as BMW has shown us.

So let’s return to our original question: what would Apple gain from entering the car market? In short, not much. Our three part analysis has shown that the automotive industry isn’t nearly as profitable as consumer technology. Of course, profits aren’t everything, and Apple’s goal when entering into the automotive industry could be a nobler one. But you would be hesitant to spend dozens of billions of dollars on a business that won’t return them to you. For this reason, I have come to the conclusion that Apple will not enter the car business as it exists today. If they do enter, it will have to be with something totally different. We’ve touched on what that difference could be in Part II, so I won’t go into that here, but it cannot simply be a superior version of a gas-powered car. Success might come from a place Apple has been before: Think different.

For next week, we will explore some strategies Spotify can take to combat the impending Beats (by Apple) release.

If you have anything to add, or just want to share your meandering thoughts about what we covered, please comment below! I’m also very active on Twitter, so don’t hesitate to @lsukernik me!