What is Happening at Tesla?

If we want to reduce poverty and misery, if we want to give to every deserving individual what is needed for a safe existence of an intelligent being, we want to provide more machinery, more power. Power is our mainstay, the primary source of our many-sided energies. - Nikola Tesla

I thought long and hard about the perspective from which I would be writing this post. On the one hand, Tesla is the underdog car manufacturer, in combat with gas-guzzling titans. On the other, it is a company that creates batteries that just happen to have four wheels attached to them and get you from point A to point Z. After several hours of deep-thinking and consternation, I settled on an answer. The answer came from Tesla’s 2014 Annual Report, after reading what Tesla identifies itself as (emphasis mine):

“We design, develop, manufacture and sell high-performance fully electric vehicles, advanced electric vehicle powertrain components and stationary energy storage systems. We have established our own network of sales and service centers and Supercharger stations globally to accelerate the widespread adoption of electric vehicles. We believe our vehicles, electric vehicle engineering expertise, and business model differentiates us from incumbent automobile manufacturers.”

As analysts, we are often quick to jump to conclusions, but let’s repress that instinct for this post. Personally, I’ve always viewed the word “vehicles” to represent cars, trucks, and motorcycles. But vehicles are actually much more than that - they're a mechanism for transportation. I bet the same objects come to your mind when you hear the word vehicle, in part because traditionally, that is what vehicles were, and still are to this day. Tesla isn’t a battery company, as many are led to believe. It’s a transportation and energy company based on electric technology.

Today, that technology finds its habitat in the Model S, which is Tesla’s premium four door sedan. Later this year, that electric technology will be crammed into the Model X, a crossover between a SUV and a minivan. In 2017, we will have the Model 3, a lower-priced sedan, as electric technology becomes cheaper to manufacture and consequently moves downmarket. It isn’t too hard to see a future where this electric tech will be found in bikes, trains, helicopters, airplanes, and other vehicles of transportation. In short, Tesla is in the business of providing energy.

That’s the future of Tesla, but the present is the presence for this post. Let’s take off our rose-colored glasses for a second, and view Tesla with more conservatism (as accountants such as myself are classically trained to do). What is currently going on in Elon Musk’s lair?

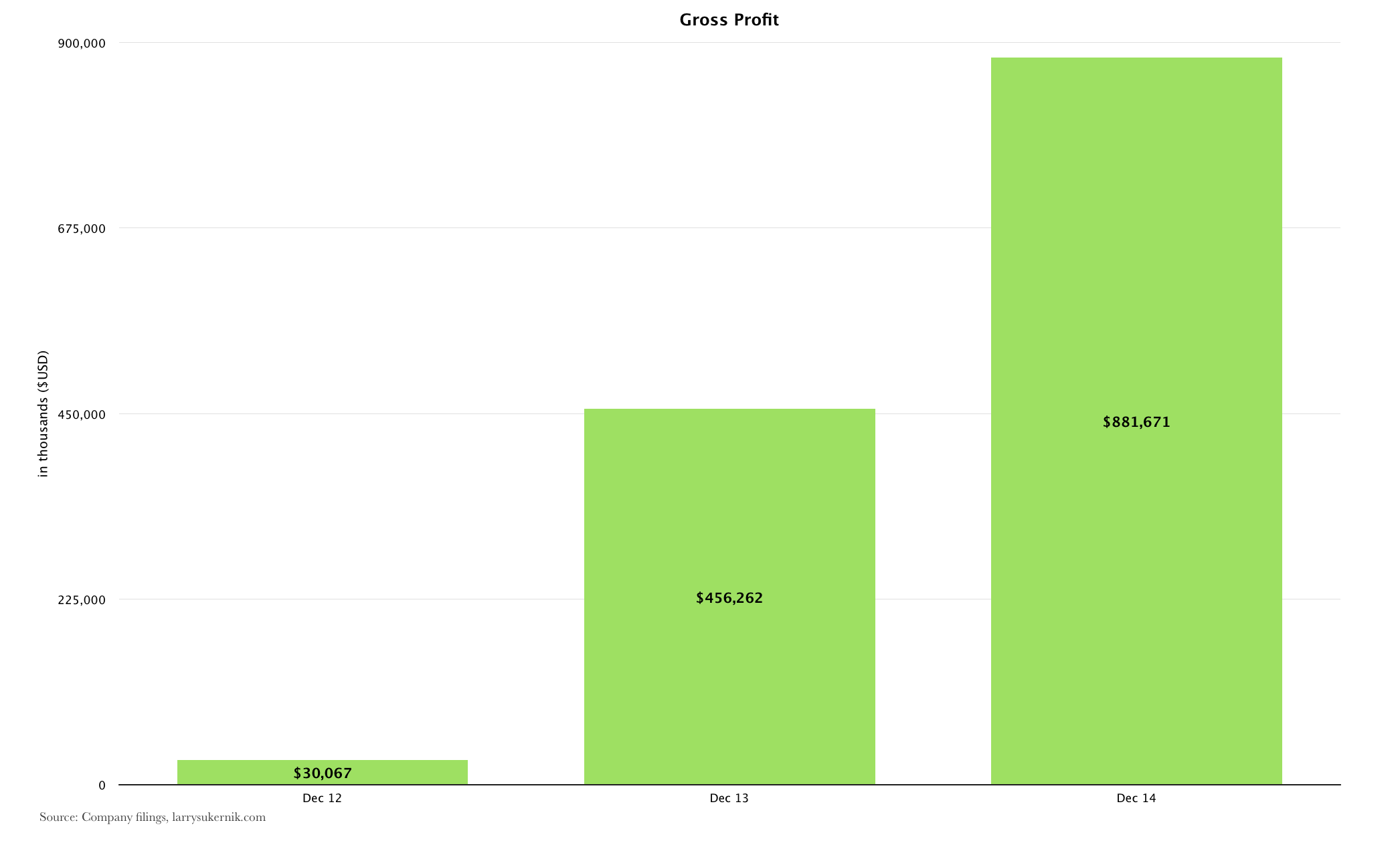

Revenues have been growing rapidly at Tesla $386M in 2012, $2B in 2013, and $3.2B in 2014. By my calculations, Tesla will generate $5.6B in revenues in 2015, mostly due to production improvements and the introduction of the Model X in 3Q15. Tesla’s revenues could actually be much higher - they’re held back by supply. The faster Tesla is able to manufacture more cars, the faster revenues will grow.

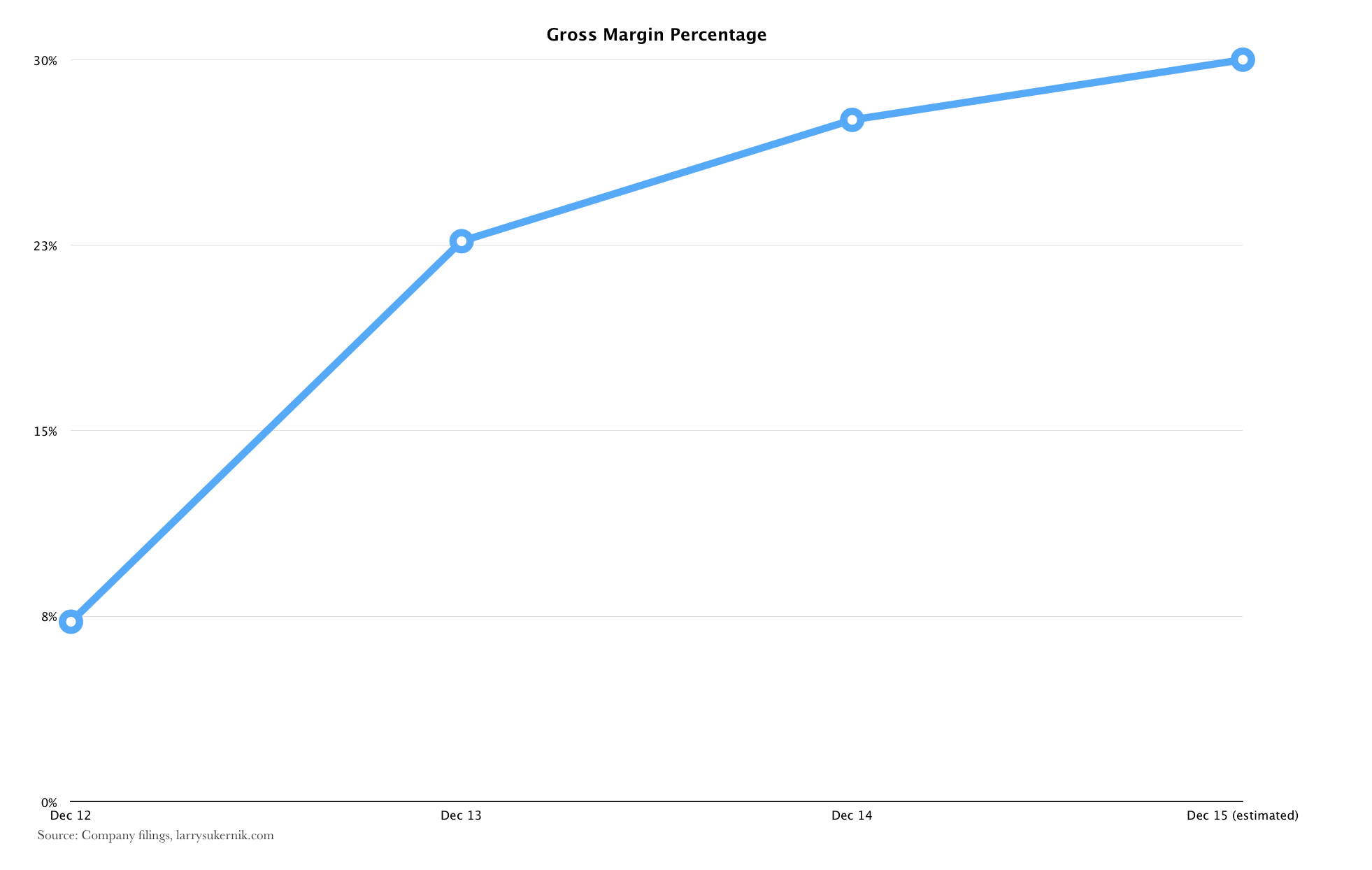

As we’ve discussed before, automotive industry profit margins are nothing to be jealous of. Traditional car company gross margins range from 11% (GM) to 26% (Honda). Tesla beats them all, with 28% margins. Unless you work as an accountant for Tesla (if so, please do not hesitate to contact me), it’s difficult to say with certainty why Tesla commands the highest margins. That said, I can offer a few pontifications.

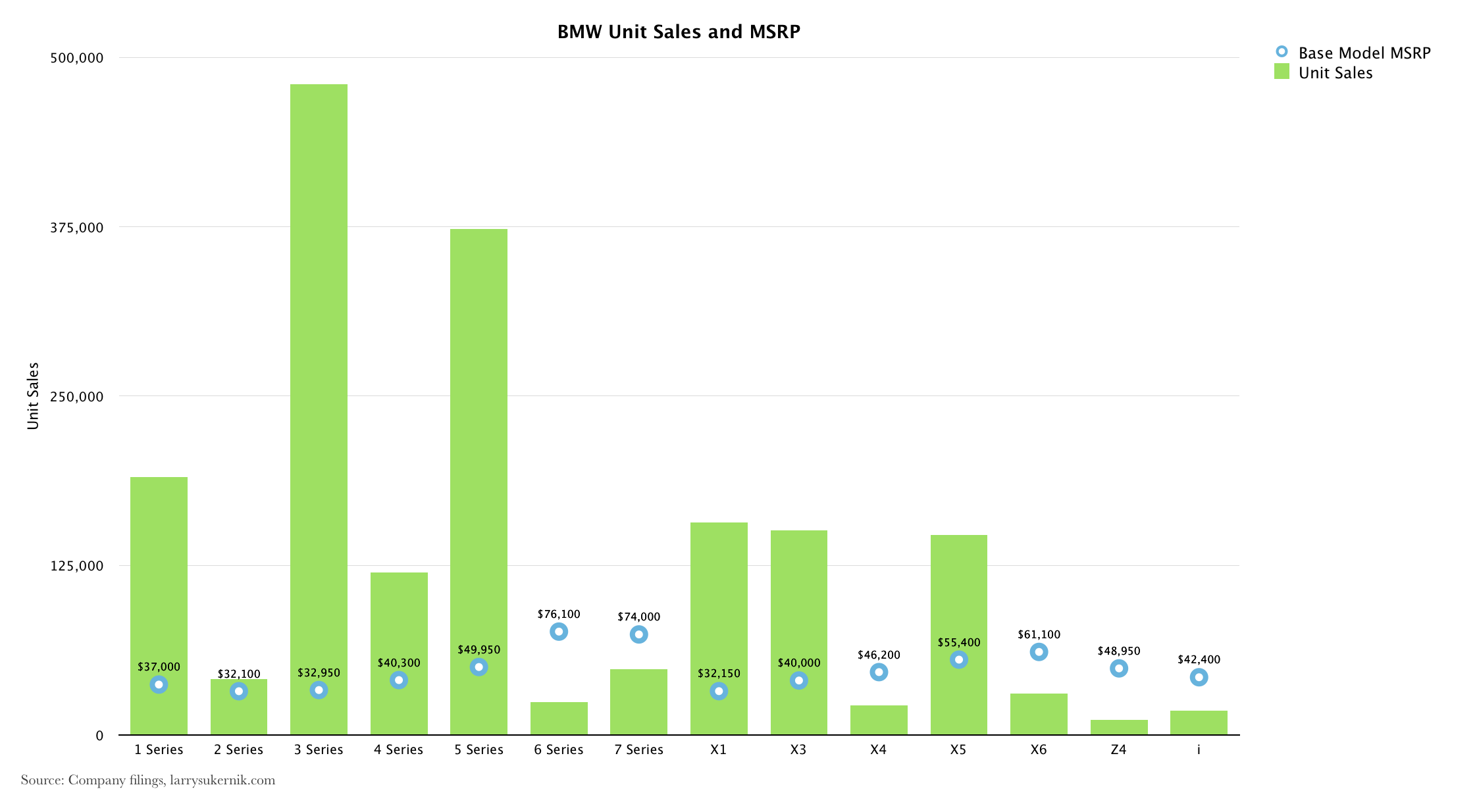

Tesla is a premium car brand and charges premium car prices. The starting price for a Model S is $70K, but the average revenue Tesla makes per car is approximately $97K (not a perfect comparison, but a Honda Civic starts at $18K). Obviously the margins will be much higher for expensive vehicles, which Tesla is in the market of producing. It will be interesting to see if margins will remain high once Tesla releases the Model 3, which is supposed to start at a much lower price-point.

Tesla margins may also be high because of lower cost of revenues, which in English means cheaper parts (in relation to the selling price of the car). Most gas-powered cars use an internal combustion engine (ICE), which has many moving parts that need to be purchased from individual suppliers. Prices for these parts tend to fluctuate - in some periods prices may go up, and in others prices may go down. As a result, the cost of manufacturing a car with an ICE can be a volatile and expensive proposition. Tesla doesn’t use an ICE in any of its vehicles. Instead, the cars are powered by an electric motor which in turn is powered by a muscular battery. Tesla’s electric motor has many fewer parts than the ICE, which I suspect is another critical reason for the higher margins.

The inefficiencies of Tesla begin to appear a bit lower in the income statement, namely with Research and Development (R&D) and Sales, General, and Administrative (SG&A) expenses, which account for 15% and 19% of revenue, respectively. In other words, $34 out of every $100 Tesla makes in car sales goes to keeping the lights on for the business! I’ve made a handy chart to see a simplified version of Tesla’s income statement, just in case the accounting minutiae goes over your head:

As Tesla grows, it should scale its operating expenditures (which include R&D and SG&A) to be more in line with the growth of revenues. In 2014, revenues grew 58% while operating expenses grow 106% - nearly twice as much as revenues! This isn’t a huge cause for concern yet, but it is something worth keeping in mind.

Tesla posted net losses of $396M in 2012, $74M in 2013, and $294M in 2014. From an investors point of view, Tesla is an extremely young company, and an insanely risky investment (Tesla paid a lot of money in interest, over $100M, to compensate creditors for this risk). That said, many great companies have initially started as unprofitable enterprises, later to become billion dollar printing machines.

What is Tesla, really?

Tesla is currently manufacturing electric cars, and viewed in that light, it’s a decent business. Tesla sold 32K cars in 2014, and plans to sell 55K in 2015. Global car sales in 2014 were 71M, so there is plenty of room for growth. But as I’ve mentioned at the outset of this post, I wouldn’t view Tesla solely as a car company, because based on that alone, the future isn’t bright. I don’t see Tesla succeeding in the car market if they continue making expensive, electric cars. Unless they get the Model 3 to very low price point (<$30K), there is a natural limit to their growth. Only so many people can afford $100K cars, and out of those, even fewer want an electric car.

When viewed as a transportation company and an energy provider, however, the future of Tesla looks much better. They would be in the business of providing energy solutions, be it vehicles or stationary power sources, which would be both a lucrative and fascinating market to enter. Cars would be just one product offering (“look how powerful our electric energy solution is in our car; would you like to purchase the same solution to power your house?”). Tesla never got the recognition he deserved during his lifetime, but the Tesla of our generation is determined to change that.

Slideshow