The Academic and The Professional

Business strategies are just like opinions, and opinions are just like you know what. Everybody has one. If you Google around, or read this blog, you will find a lot of conflicting advice that people give to companies. As with any advice, some of it is good, some bad, and some downright comical. You can categorize this advice into two umbrella categories: Academia and Experience.

Academia

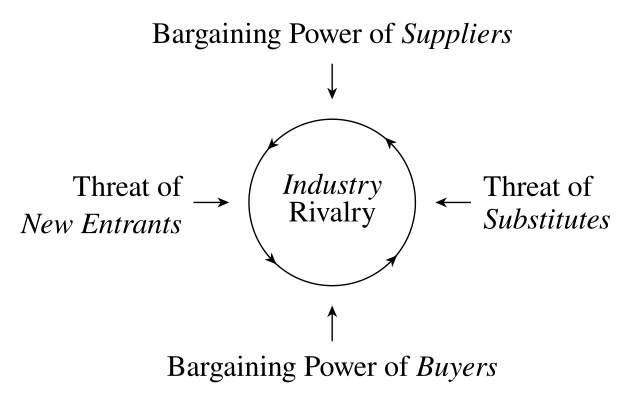

Business strategies from the world of academia are distinctly different from strategies given by an experienced professional (I use the term experienced professional because it fits rather nicely, but you can substitute it for any word that implies real world knowledge). Academic strategies are often from PhD's and business school professors who attempt to explain the world with models. These models are imprecise, but they are general templates of how a business should operate to be successful. Probably the best known model is Michael Porter's Five Forces Analysis, which seeks to develop a framework to understand how intense competition in some industries is. This is a gross simplification of the Porter's model, but I bet if you asked him to pitch it to you in an elevator, that's precisely what he would say. The problem with this model, and any model really, is that it encourages you to fit a business into it even when it doesn't fit.

To illustrate the weaknesses of models, let us take Twitter and try to explain it through the Five Forces Model.

The Threat from New Entrants

This one is relatively simple to explain. It is easy to create a new social media startup, because the barriers to entry are so low. That said, this threat is mitigated somewhat by the difficulty of starting a successful startup that effectively competes with Twitter. Many other factors are present for this threat, such as economies of scale, customer loyalty, government policy, and a slew of others.

Threat of Substitute Services

This force is also simple to explain, and the model accurately reflects the realities of Twitter's business. How easy is it to create a substitute for Twitter? Well, creating the substitute is relatively simple. All you need to make is a service that lets you share 140 characters with the world. Many mimicking services have launched in the past few years, but literally all have failed. The switching costs to a new service are fairly low for Twitter users, since it's free and few people care about their past tweets being transferred to a new service.

Bargaining Power of Customers

This is where the model starts to break down quite a bit. Who are Twitter's customers? Are they the users of the service, or the customers the people who purchase ads on Twitter? The answer isn't clear and can be argued both ways. Incorrect use of the model can get a business in a lot of trouble, which you can say is the failing of the business and not the model. While this is probably true, business models are not like scientific models. People are must more open to accepting a business model such as Porter's Analysis when compared to a scientific model that sets forth a hypothesis. This results in business models that are often treated as gospel.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Traditionally, suppliers provided raw materials or some other basic ingredient/service to your company. You can see why Porter factored this into the model, since a powerful supplier could seriously undermine your business. But in the age of the internet, suppliers aren’t nearly as important to web companies like Twitter. This isn’t to say that Twitter doesn’t rely on any suppliers, because they probably rely on dozens of companies. It’s just that this factor is of such minuscule importance that it’s a nuisance to even include when evaluating most web companies.

Intensity of Competitive Rivalry

The problem with this factor is that it’s so comprehensive that a whole model can be built just to understand it. Surely Facebook is a rival of Twitter, since both are popular social networks. But than what about Path, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Yelp, Foursquare, Snapchat, and Tumblr? Isn’t the ultimate competition for the users time? If so, these companies (and many more) would be a competitor to Twitter. It’s worth noting that some are closer competitors (Facebook) and some farther (Foursquare), but my point remains: this factor is totally open-ended.

The goal of this exercise wasn’t to display my Porter Analysis prowess, but to walk you through its strengths and weaknesses. The greater goal, however, was to exemplify how models are used in the world of academia. Porter’s analysis is just one of many academic models, which are all somewhat similar to each other. That is, the world of academia attempts to create models that are comprehensive and general. They seek to explain whole market segments and industries, by citing common trends within these areas.

In a way, these models are naive. Human nature is such that it wants explanations for things, even when the explanation isn’t totally correct. While Porter’s model is extraordinarily helpful in understanding the rivalry within an industry, it suffers from being overly academic. His Five Forces fits for the industries he studied, but as we have seen, they don’t entirely fit Twitter. To try and wedge a web company like Twitter into his model would be to grind coffee with a knife. It might seem like I’m picking on Porter, but almost all of the academic models I have studied suffer from the same broad-stroke failings. The tech community has fully embraced Clayton Christensen’s disruptive innovation, but it is also too comprehensive for its own good. Academia follows the same thinking pattern that it teaches to its students. It would be silly to teach business school students specific strategies applicable in particular industries for distinct companies, so instead, professors focus on high-level theory. Unfortunately, the very same theory they teach becomes the strategic model they attempt to apply to a real-world company, and it simply won’t fit.

Experience

The second general category of business advice comes from the experienced professional. This is a person who has worked in an industry, or has specifically followed an industry, for years. Examples that come to mind are consultants, analysts, and C-suite executives who have held important roles within a company. These people usually take a different stance on business strategy - one that is much more nuanced and specific. Consequently, the experienced manager will give advice that is highly specific to one company, and this advice is usually never applicable to other companies. An experienced professional who works for Twitter might argue that keeping their API closed to third parties, effectively limiting the amount of complement products, to Twitter is a good idea. This would obviously be bad advice if applied to another company such as Dropbox, since they want to have their cloud storage available everywhere. The experienced manager does not build models, and instead circumvents them in order to get right to the problem. Business is a touchy-feely and free-flowing animal, while academia models are more rigid.

The experienced professional has his own failings too. Experience is usually narrow and applies to niches. Experience in one company might not apply to the next company the manager joins. It can lead to the overconfidence bias, which may actually hurt performance.

The Academic Professional

After everything I have written above, you could ask why doesn't the experienced professional just read some academia books to embrace the best of both worlds? And you would be right, since that is exactly what any business minded person should do. Both categories of business strategy have failings and biases, which can be circumvented by not fully buying into one way of thinking. Academics shouldn't be so confident about their models, because nothing in business is so black and white. A model that works during this decade might not work the next decade, and you often see businesses have trouble letting go of their old strategies that are no longer applicable. Similarly, the experienced professional should educate himself in the general trends some industries follow, but at the same time he must realize these models are just oversimplifications. Being able to maneuver and shape a model to the realities of the real-world is key to applying it right.